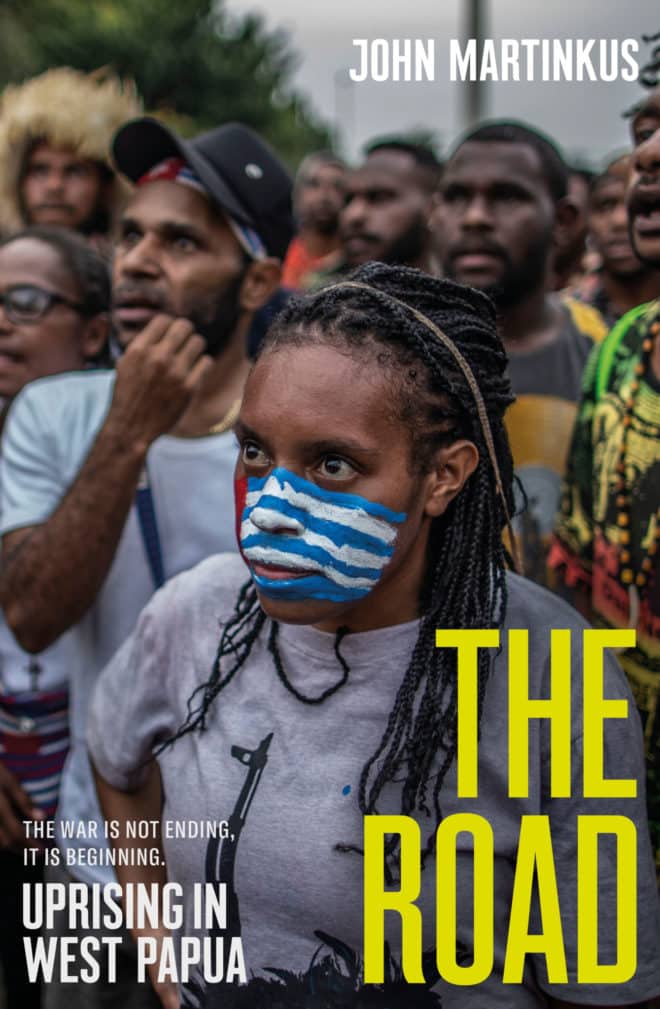

Jayapura, Jubi – Eighteen years after the publication of his Quarterly Essay entitled “Paradise Betrayed: West Papua’s Struggle for Independence”, John Martinkus’ book, The Road: Uprising in West Papua, has been released. Much has happened in the almost two decades spanning the publication of these works, but some basic facts remain the same: the people of West Papua are facing a brutal military occupation of their homelands by the Indonesian military.

Extensive violence and human rights violations are a routine occurrence in the region. The interests of multinational resource extraction companies are routinely placed above the livelihoods of the people whose land they operate on, and attempts to report on this situation are made exceedingly difficult by an almost non-existent freedom of the press. An Australian journalist who has worked in combat zones for decades, Martinkus has reported on the situation in West Papua for most of this century. Since 2003 the Indonesian government has not allowed him to return there.

The road mentioned in the book’s title refers to the Trans-Papuan Highway, a 4,300-kilometre-long construction project spanning the length of West Papua. This road plays an important symbolic function for Indonesian nationalism. Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia, imagined a unified Indonesian nation from Sabang, an island on the coast of the far-western tip of Aceh, to Merauke, a town in the furthest south-eastern corner of West Papua, where it is planned the highway will terminate. The completion of the Trans-Papuan Highway would fulfil Sukarno’s vision, and it is for this exact reason that the West Papuan people, most of whom have never accepted Indonesia’s claims to their territory, are adamantly against its construction.

Aside from its symbolic function, the road would further facilitate the expropriation of West Papuan’s natural resources by multinational companies. From the decisions about the legal status of the region in the 1960s until the present day, the interests of multinational resource companies have been prioritised over the interests of the people of West Papua.

In 1967, the late Indonesian president, Suharto, awarded the US company Freeport-McMoRan a contract to open the Grasberg mine, the world’s largest gold mine and second largest copper mine. Freeport-McMoRan are the single largest taxpayer to the Indonesian government. This mine has been consistently opposed by the local West Papuans, and in 1977 a section of the independence movement managed to halt its operations. The result was the killing of 800 Papuans, and Martinkus cites evidence that Freeport itself had paid for equipment and weapons used by the Indonesian military in this violent crackdown. As recently as March this year there have been renewed reports of fighting in the town of Tembagapura, near the Grasberg mine.

It is these accounts of more recent events in the freedom struggle that makes Martinkus’ book especially valuable, placing them within the context of the historical movement for independence. A statement released in May by West Papuan activist-in-exile Benny Wenda informs us that since December 2018 over 45,000 West Papuans have been internally displaced, and that the Indonesian military is using the coronavirus pandemic as a way to conceal their recent actions. Martinkus shows us that while the oppression faced by West Papuans is not abating, the resistance to it is, if anything, intensifying.

He details the waves of protests in August last year in cities across West Papua, sparked by an incident where West Papuan students in the city of Surabaya, on the island of Java, were subject to racial abuse. The protests gathered thousands of people and reached an intensity that shocked the Indonesian authorities; government buildings were burnt down, as was a prison, leading to the escape of 250 prisoners. In the realm of diplomacy, last year also saw the delivery of a petition to the United Nations that had garnered 1.8 million West Papuan signatures, out of a total population of 2.5 million, requesting that the West Papuan region be re-listed as an area of concern for the UN Special Committee for Decolonisation. The struggle for independence is ongoing and Martinkus’ book is current affairs journalism, not history.

Near the end of the book Martinkus writes that:

I was in Iraq at the height of the American occupation, Sri Lanka at the height of the campaign to crush the Tamils, Burma at the height of the campaign against the Burmese people and the minorities who stood against the military, East Timor and Aceh under the Indonesians, Afghanistan in Taliban-controlled areas [but] never have I seen a people more systematically oppressed and isolated than the West Papuans […]

In a book that is well-researched and resistant to sensationalism, such a statement is astounding to read. We should consider this claim alongside the fact that the Australian state, through its diplomacy, economic interests, military training, and aid, has actively facilitated the Indonesian occupation of West Papua and the abuses and violence that have occurred there – there being, as Martinkus reminds us, “only a day’s ride in a tinnie with an outboard to Australia across the Torres Strait”. The Road is an invaluable resource which deserves to be read by a wide audience looking to learn more about the history and recent developments of the independence struggle in West Papua. (*)