By Nico Syukur Dister OFM

As in Papuan society, so also in churches, there are members who opine that the western part of New Guinea has the right to be an independent state. There are also members who consider this region the provinces of the Republic of Indonesia. But how is the attitude of the several church leaders?

Seen from a theological point of view it is the duty of the ecclesiastical hierarchy to unify the faithful. That’s why bishops and pastors think they are not allowed to take side with one of the two attitudes mentioned above, and against the other. However, the real-politics in West Papua makes it impossible for churches to remain neutral and hide their position.

Recently, leaders of three Papuan churches (GIDI, BAPTIST and KINGMI), whose members and leaderships are predominantly native Papuans gathered as “Ecumenical Work Forum of Papuan Churches”, released a pastoral letter condemning the ongoing violence and discrimination against Papuans. These church leaders said to their faithful that because of so many cases of violence, detentions, tortures and killings of civil Papuans, “there is no future for the Papuan nation within the Indonesian system.” As far as I know, the Catholic Church seldom or even never made such a clear statement. Why is that the case?

In the Catholic circle, people often say, “Of course the Church will not frankly support the call for Papua’s independence, but we unanimously raise the injustice that occurs.” This statement needs to be scrutinized. First, the question of Papuan independence seems to be a political subject. But the distinction between politicians’ concern and the church’ concern has lost its relevance from the moment we ask whether or not every nation has a right to own a country. Many Papuans think about themselves as a nation and not as a tribe within the Indonesian nation. Their decolonization process was interrupted by manipulative international politics and Indonesian military infiltrations in 1960s. This complicated historical process, combined with military oppression, human rights violations, marginalization, and resources exploitation caused their integration into the Unitary State of Indonesia more like a colonial occupation than decolonization. With respect to that reality, isn’t it an injustice that Papua is not yet independent, hence should not it be part of the church’ concern “to raise jointly the injustice that occurs in Papua”?

Non-violent struggle for Self-determination

Culturally, Papuans belongs to Melanesian culture and not Malay as other tribes in Indonesia. It also has different historical trajectory. While Indonesia proclaimed its independence in 1945, Papua remained under the Dutch rule until 1963. The Papuans, who wanted their independence as much as other colonized nations in that era, were promised by the Dutch authorities to have its independent nation state by 1970. At the same time, Indonesia, who claimed Papua as part of its territory, gained support from its allies, leading to the New York Agreement 1961 which stipulated the transfer of administration of Papua from the Netherlands to Indonesia. It also stipulated that Indonesia would organize a UN supervised referendum no later than 1970 through which the Papuans could decide to join Indonesia or have their independent state.

The referendum did take place in 1969. However, the referendum is in fact a legal defect for two reasons. First, the way it was carried out was contrary to the agreement of one man, one vote. The referendum was in fact an agreement made by 1,025 men and women selected by the Indonesian military administration. Instead of voting, they raised their hands or read from prepared scripts in a display for United Nations observers. Second, the UN General Assembly made the result legally binding, without taking cognizance of the abuses reported by the UN delegates themselves (Drooglever 2005, Saltford 2003).

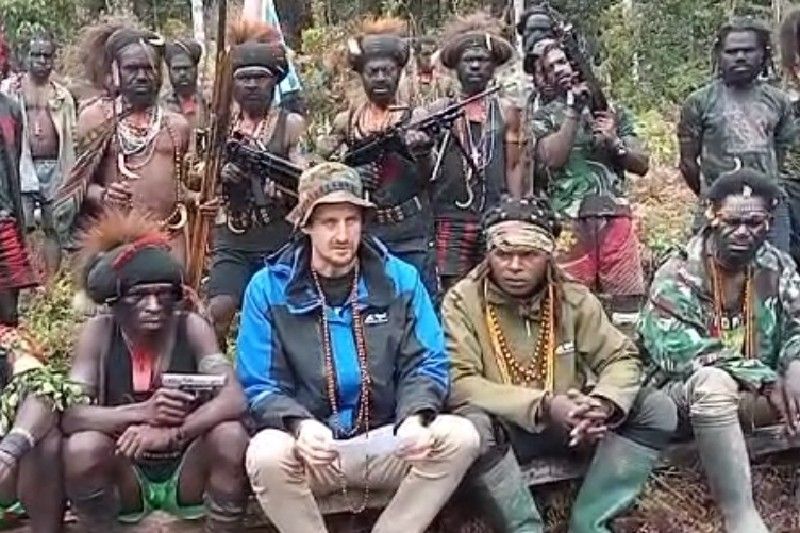

My argument is: as long as the indigenous Papuans don’t get what is due to them in justice, any development and material relief from Indonesia cannot extinguish the fire of independence struggle. It keeps burning in the heart of each of them. More and more Papuans, including the Christian ones, get involved in non-violent struggle. They realize that arms struggle only means harm and suffering. Hence they fight in Mahatma Gandhi’s manner: no violence, ahimsa, a resistance strategy that delivered India from the evil of colonialism.

The Catholic attitude

The church does not only consist of bishops and other clergy. According to the Jayapura Diocese after its pastoral synod in the seventies, “We are the Church”. Nevertheless, we may hope that the pastors are good shepherds who lead the way and march in front of the flock. To the church as a whole –both leaders and members—the prophetic mission has been entrusted to blame, criticize and correct abuses, for the purpose of bringing back the faithful and the society into the right direction.

In Papua when representatives of other churches heavily and loudly protest as part of their prophetic mission, people ask: “Where is the voice of the Catholic church”? Oftentimes its voice cannot be heard, because Catholic leaders prefer to speak with the responsible “dignitaries” of army, police and government in private meetings. Many Catholic bishops and pastors consider such a talk more effective than protesting publicly. They are also convinced of their duty to build bridges between two opposing parties. But whether such a private talk is more effective than a loud protest that resounds in the media is questionable. The worsening of the human rights situation in the recent years does not prove that this “Catholic approach” is more effective.

I think in order to play an important part in the Church’s prophetic mission, the Catholics and their leaders must speak publicly and very loudly against every human rights violation in West Papua, while at the same time, on one side, respecting the political conviction of each parish member and citizen, either pro-Unitary State or pro-independence, and on the other, explaining why an aspiration for independence is something genuine, especially when pursued without violence: ahimsa.

Father Nico Syukur Dister, OFM is Professor at the “Fajar Timur” School of Philosophy and Theology in Jayapura,