By : Roshni Kapur

The province of West Papua continues to be shrouded in secrecy from the rest of the world. West Papua’s struggle for independence from the Indonesian government has been simmering for half a century. The conflict has received little media coverage since the Indonesian government has managed to block and censor information. The government has also implemented a policy that bars foreign journalists from entering West Papua, hence preventing stories of human rights violations from being reported and reaching the outside world.

West Papua was the only territory of the East Indies Empire which the Dutch did not give to Indonesia. In 1961, the Dutch formed a national assembly and the Morning Star flag was hoisted declaring its independence. Soon after, Indonesia invaded West Papua with the military support of the Soviet Union.

The US intervened by brokering the New York Agreement without consulting or involving the indigenous people. The agreement gave Indonesia interim control of West Papua until the 1969 Act of Free Choice, a UN-sponsored referendum to vote for either independence or integration will be held. Instead of holding a universal referendum, only one per cent of the population was handpicked to vote. Those selected by the authorities were intimidated with force which resulted in a unanimous vote that was in favour of joining Indonesia.

Although the outcome of the referendum was unopposed around that time, many West Papuans think that their mandate was not taken into account on whether they want to be a part of Indonesia. The Indonesian government wrests their control of West Papua through the New York agreement.

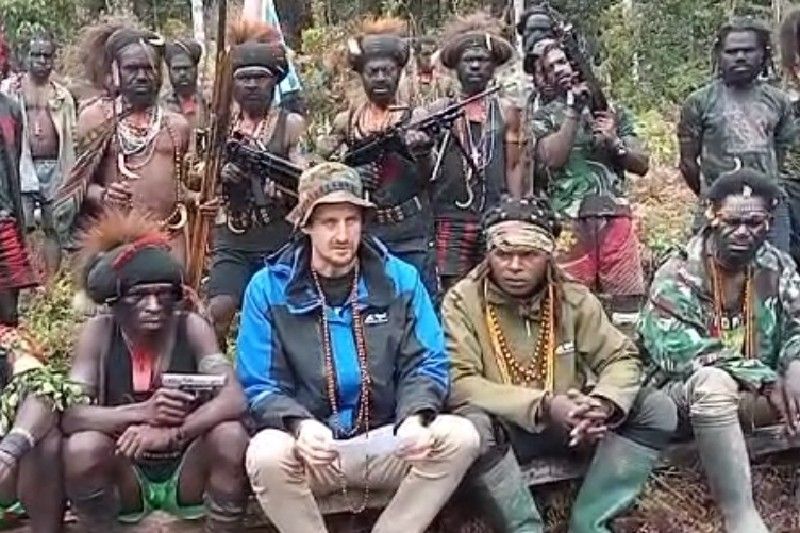

The West Papua resistance is the most protracted conflict in the Pacific which is a highly sensitive issue for Indonesia. Almost 500,000 people have been killed since Indonesia’s annexation in 1969. The province is the most heavily militarised place of Indonesia with around 45,000 military personnel currently deployed. In 2012, security forces deployed in Wamena ambushed civilians and burned down houses and vehicles. The violence continued where in May 2015 some 487 activists were arrested for taking part in the signature-raising campaign, where some were subjected to torture.

Jokowi’s administration

There have been high hopes that the incumbent Indonesian president Joko Widodo may bring in new reforms on Indonesia’s policy towards West Papua. He granted release to five West Papuan inmates and removed restrictions on international media during his visit to the province in May 2015.

“The Jokowi administration has been trying to improve the human rights, economic, and security conditions in Papua,” DrIkrar Nusa Bhakti, a research professor at the Research Centre for Politics was quoted in an online article on ABC.

“Mr Jokowi has visited Papua four times and become the first Indonesian president (to) spend his time and attentions on Papua,” he added.

Although Widodo has tried to pacify Melanesian leaders that Indonesia upholds democracy, the police continue to use unrestrained force on West Papua.

The UN now faces regional pressure to probe the alleged human rights violations in West Papua. In March 2017, seven Pacific countries, led by Vanuatu, pushed for an UN inquiry into the alleged human rights abuses such as extrajudicial executions, fatal shootings and beatings of nonviolent protesters.

The appeal on behalf of the seven states was made by Vanuatu’s Justice Minister Ronald Warsal during a session in the UN Human Rights Council who requested for a detailed report from the high commissioner for human rights.

“To date the Government of Indonesia has not been able to curtail or halt these various and widespread violations,” he said.

“Neither has that Government been able to deliver justice for the victims. Nor has there been any noticeable action to address these violations by the Indonesian Government,” he added.

In response, Indonesia has denied that human rights abuses are rife in West Papua and criticised the countries for meddling into its affairs.

“The Indonesian Government has always endeavoured to address any allegation of human rights violation as well as taking preventative measures and delivering justice,” an Indonesian Government spokesperson told the Human Rights Council.

Some think that chances remain slim for an UN supervised referendum without approval from the Indonesian government who is ferociously against holding another referendum. West Papua’s mandate for liberation is the government’s biggest nightmare.

“The TNI (Indonesian Armed Forces) has made very clear it will not allow it, and no president has sufficient political will or capital to push it that hard,” Damien Kingsbury, Professor of International Politics at Deakin University in Melbourne was quoted in an online article on Pasifik News.

On the other hand, others think that the heightened awareness from the unwavering and persisted self-determination struggle may be a positive step.

“We need to look at what the movement has been able to achieve in recent years in terms of raising the profile of this issue not just in our region but across the world,” said Tess Newton Cain, political analyst from the Vanuatu-based TNC Consulting.

High-profile politicians such as Britain’s opposition Leader Jeremy Corbyn have also backed the resistance movement, calling for a political strategy for West Papuans.

“It’s about a political strategy that brings to worldwide recognition the plight of the people of West Papua, that forces it onto a political agenda, that forces it to the UN, and ultimately allows the people of West Papua to make a choice about the kind of government they want and the kind of society in which they want to live,” he said during a meeting of the International Parliamentarians for West Papua at the House of Commons in the UK.

The mountainous region, comprising the provinces of Papua and West Papua, is home to more than 250 Melanesian ethnic groups. The tribes have not shown any inclination to join Indonesia, a country with which there is no common culture, history, ethnicity or religion. West Papuans belong to the Melanesian race. In 2007, the province’s name changed from West Irian Jaya to West Papua to fulfil the aspirations of the indigenous people.

Indonesia’s sovereignty of West Papua is recognised by most countries including the US and Australia. Australia has said that Indonesia’s rule over the region Papua provinces is defined by the 2006 Lombok Treaty. However, many Pacific island countries think that another referendum should be held to decide West Papua’s sovereignty.

The province is a poverty-stricken region even though it is one of the most mineral-rich areas in the world. According to the Australian Institute of International Affairs, the poverty level in the province is thrice more than Indonesia’s national average.

Indeed secession movements against an occupation are a tall order where the propensity of achieving full secession is grim. The self-determination resistance will continue until West Papuans are not given the freedom of choice to decide about their political future. Getting outsiders involved in the movement might be one way to push for democratic reform that will restore the dignity, freedom and respect for them. (*)

Roshni Kapur graduated from the University of Sydney where she specialised in Master of Peace and Conflict Studies. Her research interests are in the areas of women’s rights, civil society, and migration, conflict transformation and reconciliation.