Papua, Jubi – Indonesia’s president called on police Thursday to act against officers who allegedly made racist taunts that provoked days of unrest in the volatile Papua region, but a Papuan man told BenarNews that locals felt nervous about wandering outside during a fourth day of anti-Jakarta protests.

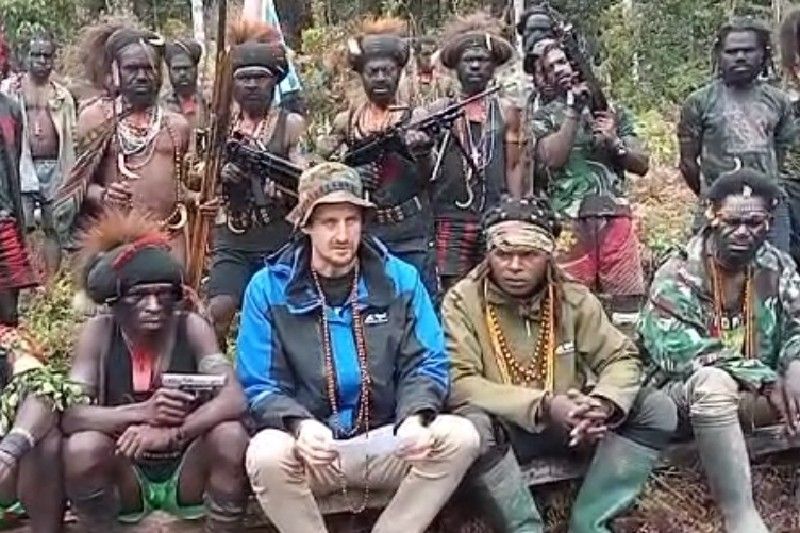

Pro-separatist activists from Papua became enraged and took to the streets over accusations that Indonesian government security personnel and vigilantes had used racial slurs such as “monkeys” and “dogs” against Papuan students, as well as roughed them up while they were demonstrating in East Java province last week.

“I have ordered the national police chief to take firm legal action against racial and ethnic discrimination,” President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo said, in an apparent reference to the alleged slurs directed by law enforcement personnel against Papuan students.

“Apologies have been made, and this is a testament to our big hearts as a nation,” he told a news conference at Bogor Palace. Jokowi added that he had invited Papuan community leaders to the presidential palace on the outskirts of Jakarta to meet with him next week “to discuss ways to improve prosperity” in deeply impoverished Papua and West Papua provinces.

Minister: ‘Papuans are our golden children’

The protests broke out on Monday, when thousands of people demonstrated in major towns in Papua and West Papua provinces to vent their anger against racism and call for a referendum on independence for the mainly Melanesian region. Some of the protestors set government buildings on fire, and violence protests spilled over into Tuesday and Wednesday, when a market in Fakfak was destroyed by a blaze.

Smaller protests took place in Papua and in Jakarta on Thursday, while Indonesian officials said that internet services in the far-eastern region remained blocked as a measure for restoring order. On Tuesday and Wednesday, the central government deployed 1,500 security personnel – mostly police officers – to the region to help maintain law and order, according to officials.

On Thursday, Security Affairs Minister Wiranto, along with the chief of national police and the head of the Indonesian armed forces (TNI) visited the Papua region in a collective effort to calm tensions.

“We are here … to shake hands with our brothers and sisters,” Wiranto said on television.

“There are always bad apples, and surely there will be legal action,” the state-run Antara news agency quoted him as saying.

“Don’t make sweeping generalizations that all other ethnic groups insult ethnic Papuans,” he added, saying that “Papuans are our golden children.”

However, George Celcius Auparay, an aide to the governor of West Papua, said Papuans were hurt by the perceived race-based insults.

“We have agreed to be one nation, but why are we being treated like this?” he said, adding there should be a presidential decree banning insults targeting the Papuan people.

Meanwhile in Jakarta on Thursday, dozens of Papuan activists rallied outside the army headquarters in the Indonesian capital.

Some carried the banned Morning Star flags, a symbol of the Papuan separatist movement, as they called for a referendum on self-determination.

The protesters chanted: “Free Papua! Free Papua!” as riot police looked on.

The crowd forced their way through a police barricade, but were stopped by military personnel. There were no reports of injuries.

In Papua province, police said they had arrested 34 people for alleged involvement in Wednesday’s rioting in Timika, a town near the giant Grasberg mine operated by the American firm Freeport McMoRan, Antara reported.

Elsewhere, Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Information Technology said the blackout on internet service would stay in place “until the situation in Tanah Papua returns to normal.” Tanah Papua is the local term for Papua and West Papua, which make up the Indonesian half of New Guinea island.

Members of the public and human rights groups criticized the move.

“This blanket internet blackout is an appalling attack on people’s right to freedom of expression in Papua and West Papua,” Usman Hamid, the executive director of Amnesty International Indonesia, said in a statement.

“In addition, the decision would also prevent people from documenting and sharing evidence of abuses committed by security forces,” he said.

Rudiantara, who heads the ministry, defended its decision to impose a blackout in Papua.

“This is for the national interest and has been discussed with security authorities,” Rudiantara told reporters.

“We’re not being repressive, unlike in some other countries. People can still make voice calls,” he said. (*)

Source: Benarnews.org