By Nithin Coca

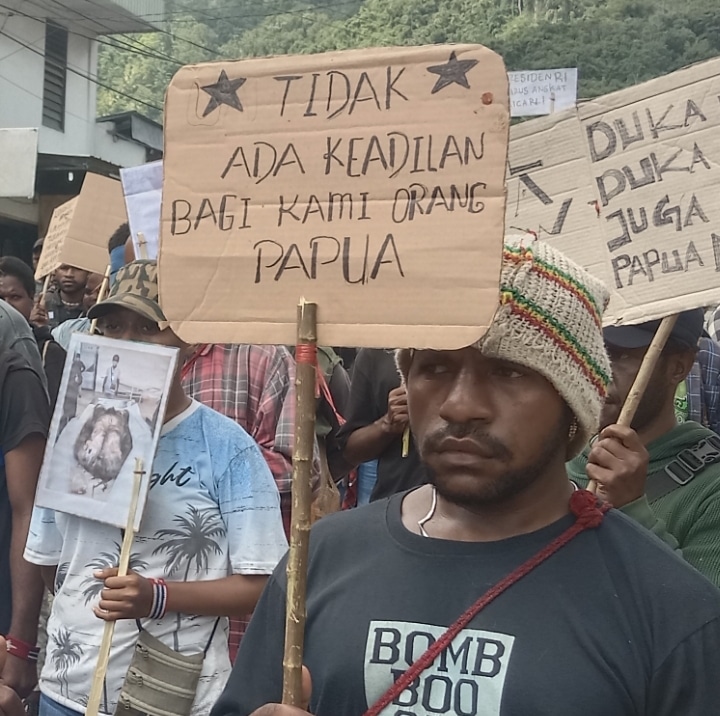

EARLIER this month, the Indonesian military raided and destroyed the offices of the West Papuan National Committee, a separatist group in the country’s easternmost region, which has long agitated for independence. The raid came amid allegations that the military had used chemical weapons in airstrikes on separatists in West Papua in late December. The Indonesian government has responded harshly after at least 17 construction workers were killed by West Papuan militants in early December, the deadliest such attack in West Papua in years.

This surge in unrest in the region is the outcome of a harder line that the Indonesian government has taken on West Papua in recent years. During the United Nations General Assembly last September, the prime minister of the tiny Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, Charlot Salwai, criticized that approach. Referring directly to West Papua, he said the Indonesian government needed to “put an end to all forms of violence and find common ground with the populations to establish a process that will allow them to freely express their choice.”

The reaction from Indonesia, which is usually quiet at the U.N., was fierce. President Joko Widodo hasn’t even bothered to attend the General Assembly in his five years in office, but his government immediately lambasted Salwai. Jakarta’s permanent representative to the United Nations, Dian Triansyah Djani, declared that “Indonesia will not let any country undermine its territorial integrity.” Referring to separatist and independence groups in West Papua, he said Indonesia also “fail[ed] to understand the motive behind Vanuatu’s intention in supporting a group of people who have [struck] terror and mayhem [on] so many occasions, creating fatalities and sadness to innocent families of their own communities.”

West Papua was not part of Indonesia when the country gained independence from the Netherlands in 1949. The region, which has a distinct ethnic and linguistic identity from mostly Polynesian Indonesia, was formally annexed in 1969 after what Indonesians call the “Act of Free Choice,” when a group of hand-selected Papuans voted unanimously in favor of Indonesian control in a vote marred by allegations of blackmail and coercion.

Since then, West Papua has been the site of regular violence, either from one of the many separatist groups on the island, or, more often, the Indonesian military. The island is rich in minerals, the revenue from which make up a significant portion of Indonesia’s budget. Freeport-McMoRan’s huge Grasberg mine alone provided more than $750 million in revenue in 2017.

Many West Papuans, either living in Indonesia or abroad, have been advocating for self-determination for years. But what was primarily a local conflict has now become more regional, as both sides have attempted to internationalize the issue. West Papuans are ethnically Melanesian, like the citizens of Vanuatu and other Pacific Island nations, such as the Solomon Islands and Fiji. West Papuan activists have been working to build connections with these countries, with the goal of having them speak up for Papuan independence, like Salwai did at the General Assembly.

“West Papua is a regional issue, because we are part of Melanesia, connected culturally and linguistically,” Benny Wenda, an exiled leader of the Free West Papua organization currently based in the United Kingdom, told WPR. “The majority in the Pacific islands, they don’t see West Papua as distant. It’s close to them.”

The main entity for cooperation in the region is the 18-nation Pacific Islands Forum, founded in 1971, and the Melanesian Spearhead Group within it, which counts the four Melanesian nations as members. West Papuan advocates have used the forum to push for global recognition, including formal membership for West Papua as an occupied country.

Indonesia, however, has been pushing back by sowing discord among the forum’s members. It provided military support to Fiji after the island’s 2006 coup, which had led to the imposition of Western sanctions, and offered significant aid to Papua New Guinea. With both countries’ support, in 2011, Indonesia was granted observer status in the Melanesian Spearhead Group. Since then, attempts by the United Liberation Movement for West Papua, an umbrella organization of independence groups, to get a similar status have proved futile. Now, both Fiji and Papua New Guinea say they support Indonesia’s full membership in the group, which would push the West Papua issue to the sidelines.

Since Indonesia got its observer status, “the MSG has become an empty house,” says James Elmslie, a political scientist with the West Papua Project at the University of Sydney. “The MSG is now split on the issue.”

Indonesia’s pressure tactics resemble the actions of a much bigger power in Asia dealing with territories it considers its own: China. Having long sought to isolate supporters of Tibet, China regularly pushes countries to refuse access to the Dalai Lama, as both Russia and South Africa have done in recent years. Beijing also uses a carrot-and-stick strategy to shrink the number of countries that recognize Taiwan, which it sees as a breakaway province. In the past year, El Salvador and the Dominican Republic have dropped their diplomatic recognition of Taiwan in favor of China. Like other countries that have done this, they can expect to be rewarded with aid, investments and more. Conversely, countries that refuse to switch, like Palau, have been squeezed by China and seen their tourism industries suffer.

Unlike China, though, Indonesia is a democracy, one that is often hailed as a model for both Asia and the Islamic world. There was a small window of opportunity, right after the fall of the three-decades long Suharto dictatorship in 1998, when newly democratic Indonesia was engaging with pro-independence activists in West Papua. At the time, East Timor was permitted to hold an independence referendum, and there were calls for something similar in West Papua.

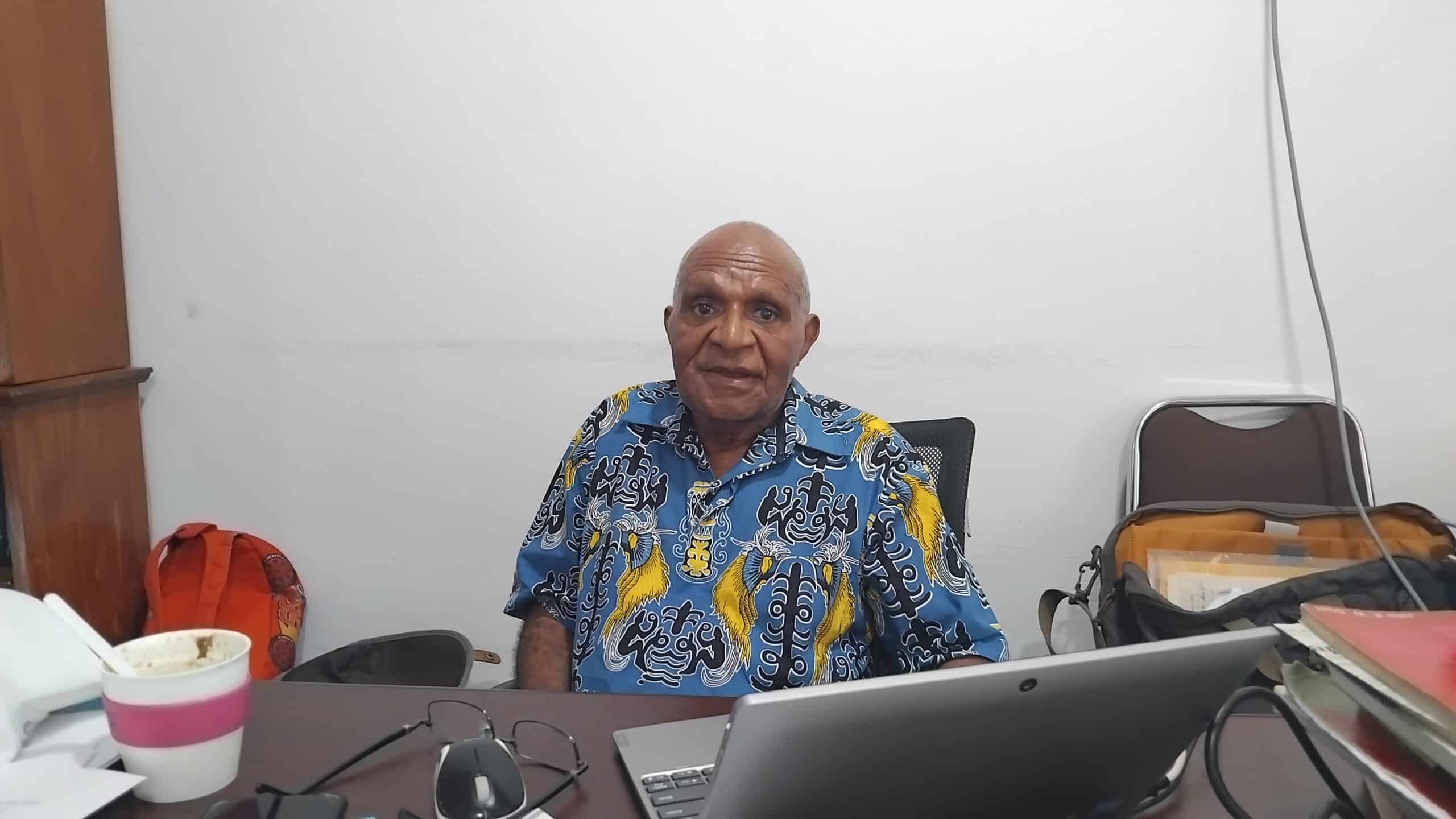

But when reformist President Abdurrahman Wahid—facing corruption allegations, economic woes and political unrest—was forced to step down in 2001, that window slammed shut. The Indonesian military reasserted control, killing Papuan independence leader Theys Eluay, and things went back to the status quo of repression. Indonesia continued to exploit the region for resources and suppress the voices of Papuans. Democracy may have transformed Indonesia, but it brought little change to West Papua.

Now the situation is only getting worse. The core problem is that unlike a decade ago, the Indonesian government is refusing to engage peacefully, instead allowing, either implicitly or explicitly, the Indonesian military to take the lead.

Getting an independent view of what’s taking place in West Papua remains as difficult as ever. For decades, the Indonesian government has essentially closed off the region to journalists, international observers and NGOs. The few who do enter face risk of arrest, like Jakub Fabian Skrzypzki, a Polish citizen who is now on trial for alleged ties to Papuan separatists and faces potential life imprisonment in Indonesia if convicted.

It looks like another move out of China’s playbook. Why would democratic Indonesia go that route? Because so far, it’s working.

Nithin Coca is a freelance journalist who focuses on social, economic, and political issues in developing countries, and has specific expertise in Southeast Asia.