By Sandy Greenberg

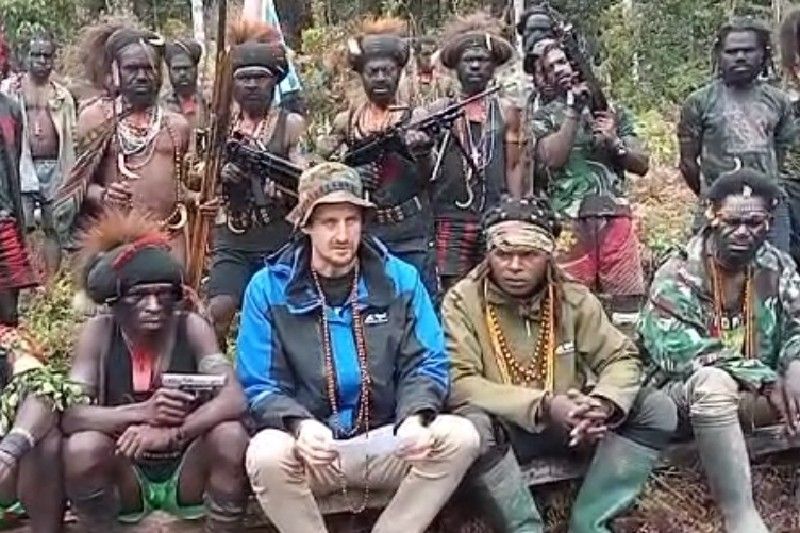

The Indonesian occupation of West Papua has been described as a “neglected genocide”, a crime against humanity being committed on a multi-generational scale, but overlooked by international observers as a matter of course. Following the departure of Dutch colonial presence in 1962, the Indonesian government had agreed to grant the people of West Papua a free and fair plebiscite between independence and integration with Indonesia, to be overseen by the United Nations. Instead, Indonesian General Sarwo Edhi Wibowo handpicked a mere 1,025 people (a fraction of 1% of the Papuan population) and forced them to vote by a public show of hands in the presence of armed Indonesian soldiers, before announcing that the vote had been unanimously in favor of Indonesian control. Jakarta justifies its control of West Papua by asserting that Indonesia is the legitimate post-colonial successor state to the entirety of the former Dutch colonies in the region; in reality, its interests lie mostly in the immense commodities wealth, principally in gold and copper, that can be extracted from its Melanesian holding. Since the occupation began in May of 1963, international media have ignored the Indonesian military as it has denied basic political rights and freedoms to Papua’s indigenous population, prevented journalists and NGOs from operating in West Papua, killed as many as 500,000 Papuans in wildly disproportionate “responses” to Papuan resistance, actively attempted to supplant or destroy Papua’s Melanesian cultural traditions (including by forcible trafficking in Papuan children), tortured Papuan political prisoners, and facilitated far-ranging ecological devastation.

Indifference to Papuans’ lives goes well beyond the media; indeed, some of the worst culprits are national governments. For many years the United States actively chose to support Indonesian claims on West Papua to prevent a shift in the Cold War balance of power (Indonesia during the Suharto dictatorship being a valued anti-communist force in the region), while today private Anglo-American mining interests unashamedly bankroll oppression. Similarly, the threat of lost economic activity in the form of Indonesian trade has compelled states, including Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and most importantly Australia, to support the occupation with money, votes, or rhetoric. Australia has been and remains a major source of weapons, matériel, and training for the Indonesian military, even supplying the type of attack helicopters with which Papuan villages were firebombed and repeatedly engaging in joint maneuvers with the Indonesian military. Perhaps more importantly, Australia has provided sustained diplomatic cover for the genocide (including by means of treaties signed as late as 2006) and created a hostile environment for Papuan activists, from former Liberal Party Prime Minister Tony Abbott saying in 2013, “…people seeking to grandstand against Indonesia, please don’t look to do in Australia. You are not welcome” to former Labor Party Minister of Foreign Affairs Bob Carr calling engaging in pro-West Papua advocacy, “an appalling thing to do”.

The Australian position is key because of its geographic proximity to Papua, its diplomatic capital and close links with NATO and Commonwealth powers, its military and political facilitation of the occupation, and its status as a major economic driver in the region (alongside Indonesia and ASEAN). Moreover, given that the only hope of West Papua attracting international backing is effective organizing targeted at international audiences (as has been the strategy of such groups for decades), Australia’s hostility towards and disempowerment of such advocacy precludes activists from the most effective regional platform via which they might reach these audiences. Recognizing Australia’s importance, the Widodo government has recently pushed Australia to intervene more strongly in favor of Indonesian control. In recent years, Melanesian states have sought to construct a greater degree of political, cultural, and economic solidarity between themselves, and greater visibility on the world stage, by forming the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), a body consisting of the governments of Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea, along with Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste, a pro-independence political movement in French-held New Caledonia. The United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) has sought to join this coalition, seeing as an effective means through which to gain visibility and supporters through cross-Melanesian solidarity. Though Fiji and Papua New Guinea, over which Indonesia has much economic influence, have opposed ULMWP’s application, the other three members, particularly Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands, have supported the West Papuan cause with increasingly forceful rhetoric, and continually pressed for ULMWP representation in the group. Concerned about the increased attention that ULMWP membership might cause, Jakarta has asked Australia to dissuade South Pacific nations, notably Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands but also others, from these efforts — for obvious reasons, Australia has more diplomatic capital and goodwill with these countries than Indonesia does.

While Indonesia pressures Australia to direct its crucial influence to maintaining the occupation, Canberra could also choose to use its influence to end the slaughter. Public Australian recognition of West Papuan cause would attract much higher media attention. Australia is well-placed to call upon diplomatic partners and work towards shaping a powerful multi-national bloc for self-determination, possibly supported by the post-Cold War UN. Moreover, by giving asylum and aggressive support to Papuan activists Australia could amplify their activism and keep them safe from Indonesian reprisal (Australia has, in the past, provided a limited number of Papuan activists with asylum, but this is neither a consistent policy nor applied to anything other than trivial numbers of people). Some Australian political factions have called for such a course of action, notably the Australian Greens. However, there exists a broad consensus between the leaders of both major Australian political camps (Labor and the Liberal-National coalition) against providing any meaningful support for West Papua. That consensus is misguided. Even putting aside questions of moral obligation or the inherent value of human life, even constraining ourselves entirely to an unalloyed realpolitik, it would be in Australia’s best interest to end its complicity.

Australia is well-placed to call upon diplomatic partners and work towards shaping a powerful multi-national bloc for self-determination, possibly supported by the post-Cold War UN. Australian politicians who fear a loss of economic activity from alienating Indonesia are correct in noting the deep economic links between Australia and Indonesia. Each country represents about 3 percent of the other’s export market, with bilateral trade growing in recent years at an average annual rate just over 7 percent. In 2012, the two nations signed the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), and each applies most favored nation status (or its equivalent) to the other’s imports. However, estimations of the actual fallout from alienating Indonesia tend to be greatly overstated.

For one thing, a significant percentage of Australia’s exports to Indonesia are beef and cattle. Because of proximity, Australia can supply beef to Indonesia dramatically less expensively than any other major beef-producer in the world, particularly given that Indonesian law recognizes the health and safety protections on Australian beef to be superior to those of other nearby countries that could conceivably supply beef. Because Indonesians’ beef demand is relatively inelastic, and because any other country that could supply beef in sufficient quantities would necessarily price beef exports to Indonesia far above the Australian price-point, Indonesia would have active economic incentives to continue trade with Australia, at least in the area of livestock.

Second, Indonesia is by far the largest recipient of Australian foreign aid, totaling USD 2 billion between 2005 and 2010 and USD 646.8 million in 2013-2014 alone. This gives Australia certain bargaining power over Indonesia — more than, of course, the likes of Vanuatu. Though Indonesia would almost certainly impose sanctions upon Australia in the wake of an Australian position-reversal, this consideration alone would disincentivize Indonesia from seeking to cut all trade relations with Australia. Incidentally, if Australian revenue did end up dropping significantly, cuts to this aid would present to some extent a compensatory windfall.

Finally, Australia and Indonesia are both part of the Australia-New Zealand-ASEAN Free Trade Area, which predates CEPA. Though Indonesia would certainly withdraw from CEPA should Australia support West Papuan sovereignty in any way, it’s unclear that Indonesia, and ASEAN member, would be able to force the other ASEAN nations to kick Australia out of this agreement; ASEAN operates on a consensus-voting system, so even one member state’s opposition to forfeiting significant Australian trade (and many member states do engage in significant Australian trade) would keep ASEAN, and therefore Indonesia, in the agreement. Theoretically, Indonesia could withdraw from ASEAN itself, but the intra-ASEAN free trade and political power it would lose in doing so make this unlikely. Thus, though the potential economic fallout for Australia is real, the degree of the fallout is constrained by structural and legal factors.

Further, any economic fallout would be outweighed in the long run by the geopolitical benefits Australia stands to gain by supporting West Papua. In particular, Australia needs favorable relations with small island states in the South Pacific. Currently, Australia’s policy on asylum seekers relies on “processing” facilities established in South Pacific states like Nauru. Though this policy is considered barbaric by respected international NGOs like Amnesty International, even after Australian immigration policy changes Australia will, for the foreseeable future, rely on cooperation from these island states on issues like people-smuggling. It therefore has an incentive to maintain friendly relations with Pacific island nations. In recent years, many of these very nations have become increasingly vocal supporters of West Papua; not only Vanuatu and the Solomon islands, but also Tuvalu, Tonga, the Marshall Islands, and Nauru have recently voiced their support at the UN. This being the case, support for West Papua would be one way for Australia to gain these nations’ goodwill.

When polled, Australians support self-determination for West Papua. It’s time for their government to do the same. Australia’s continued complicity in the West Papuan occupation is not only immoral. From a purely practical perspective, it’s irrational as well. (*)

Sandy Greenberg is an author at Brown Political Review