By Nithin Coca

WITH increasingly regular protests and a violent crackdown by police and the military, the contested Indonesian region of West Papua is currently seeing the highest levels of agitation it has experienced in years. Against a backdrop of Indonesia’s forthcoming general elections in April, tensions are rising over long-standing human rights violations, pro-independence agitation and lack of accountability for crimes committed by security forces.

“The situation is not improving for the better, it’s getting worse,” says Ronny Kareni, an Australian-based activist of West Papuan origin. “There is a divergence between Jakarta and locals, and that is deeply rooted in the historical status of West Papua.”

On 1 December 2018, more than 500 people were arrested in cities across Indonesia for commemorating the 57th anniversary of Papuan attempts to declare independence from Dutch colonial rule. Raising the pro-independence Morning Star flag or publicly expressing support for Papuan self-determination is considered a criminal offense against the Indonesian state.

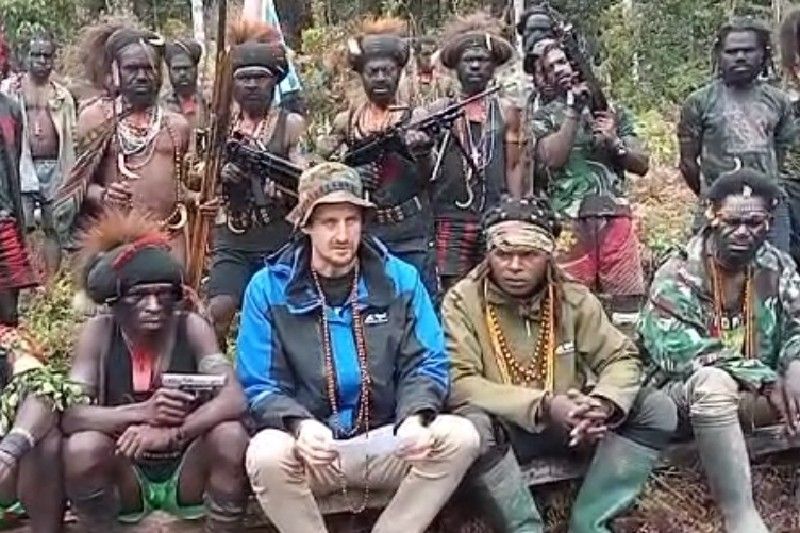

The following day, on 2 December, pro-independence militants are reported to have killed up to 31 workers on the Trans Papua Highway construction project in the Nduga region of the Papuan highlands. Although the ongoing independence conflict in West Papua has resulted in the deaths of approximately 500,000 Papuans since 1969, this was the deadliest attack by militants in recent years.

The government response has been fierce, with activists reporting that military action has forced thousands to flee their homes.

With the media and civil society prevented from independently visiting the region, these reports are difficult to verify, but international human rights organisations have made pleas for calm. “We call on all parties, the Indonesian army, police and the Free Papua guerrilla fighters, not to target civilians,” says Andreas Harsono, Indonesia researcher for Human Rights Watch.

West Papua, which forms about half of the island of New Guinea, was not part of Indonesia when it gained independence from the Netherlands in 1949. It was annexed in 1969 in a military-run election approved by the United Nations, in which about 1,000 hand-picked representatives were forced to vote against independence. West Papua was then ruled with the strongest of iron fists during Indonesia’s New Order era under General Suharto (1966-1998), before being granted special autonomy status in 2001 in a bid to quell the independence movement. The island’s population, estimated at around three million, are mostly Melanesian and follow either Christianity or indigenous religions, unlike the rest of Indonesia which is mostly Polynesian and Muslim.

Natural resources have played a significant role in shaping the trajectory of Papuan history. Shortly after the rigged election of 1969, Freeport McMoRan, an American mining company, began operating in the region. This marked the beginning of a long relationship which has proved prosperous for the company and the Indonesian government. However, tax revenues mostly go to the western part of Indonesia which is much more developed; West Papua, in the east of the country, is the poorest region in Indonesia and its people see few benefits from resource extraction.

Jokowi’s promises of reform

In 2014, then Jakarta Governor Joko “Jokowi” Widodo (now president of Indonesia), an outside candidate in the presidential elections with no connection to Indonesia’s elite or military, made several campaign promises to address human rights in Papua. This included addressing the ability of the military to use its own internal trial mechanism rather than civilian courts, opening up the region to the foreign media and freeing political prisoners. Papuans saw hope in Jokowi, and he won the two provinces (Papua and West Papua, formerly Papua until 2003) that make up West Papua by more than 30 percentage points each. In an election where Jokowi won nationally by only 6.3 per cent, the region provided him with some of his best results.

Even months after his inauguration, President Widodo reiterated his promises directly to Papuans after a police shooting in Paniai killed five people.

“Jokowi made bold promises in front of Papuans attending Christmas celebrations, saying that he would investigate and solve this case, and bring peace to Papua,” says Papang Hidayat, a researcher at Amnesty Indonesia.

Jokowi initially made a few attempts to improve the situation in West Papua by releasing five political prisoners in 2015 and declaring the region open to foreign journalists, for example. But his power has been limited due to the role of security forces in West Papua, including the Indonesian soldiers who have maintained their presence in the region despite the fall of Suharto’s military rule more than two decades ago. As a result, most of his promises to make reforms remain unfulfilled.

“It became clear to many people that whatever [Jokowi] says, it will not be implemented,” says Kareni. “He is only a face for democracy, but [he is] not actually in power.”

Harsono agrees: “The situation on the ground, especially the resistance from the bureaucracy, is much bigger than his presidential authority, I’m afraid.”

Attempting to address political grievances through economic development

One area in which Jokowi has been able to push forward is on development. The government is investing massively in roads, airports and agriculture, including a plan to build 1.2 million hectares of palm oil and sugar plantations.

Following decades of underdevelopment, “the government feels the need to pay more attention to Papua,” says Arie Ruhyanto, a lecturer in the Department of Politics and Government of Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. “Given the political setting, the option is limited to the non-political issues…hence, the Papua problem is always framed in the context of development issues, such as poverty and underdevelopment.”

In the end, this has only increased tensions, as many Papuans feel that development is either aimed at extracting resources or benefitting migrant workers from other parts of Indonesia. That’s one reason why the December attack by separatists was against the construction of the centrepiece of this new development plan – the 4,300 kilometre Trans-Papua Highway.

The response to the attack also highlights a major problem – that many in the Indonesian security apparatus do not distinguish between the peaceful protests and aspirations of the vast majority of Papuans, and a small minority of militants. In response to the Nduga attack, police arrested members of the West Papua National Committee (Komite Nasional Papua Barat, KNPB), a student-run organisation that coordinates peaceful protests, and forcefully closed their offices.

With the security forces entrenched and Jokowi’s power limited, many fear that the divide between the two sides is growing. Papuans know that the April elections are unlikely to change anything.

Gaining momentum

However, instead of waiting and hoping for action from Jakarta, more West Papuans are starting to agitate on local, national and global stages. In 2014, several West Papua independence organisations unified under the banner of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP), headed by the renowned Papuan activist Benny Wenda. The entity has been active within the 18-nation Pacific Islands Forum, founded in 1971, and the Melanesian Spearhead Group within it, which counts the four Melanesian nations of Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, as members.

“In 2015, the ULMWP put in an application bid for a membership of observer status,” says Kareni. The bid was successful. “For Papuans it was a recognition of our cause. The movement has gained a lot of momentum, especially in the Pacific.”

In 2017, organisers in West Papua undertook an impressive effort, smuggling a petition across the island and collecting signatures from 1.8 million residents – 70 per cent of the population – in support of an independence referendum, as promised in the 1960s. The petition was delivered to the United Nation’s Special Committee on Decolonization, to which Indonesia responded by arresting Yanto Awerkion, a KNPB activist and organiser of the petition drive, and sentencing him to 10 months in prison.

One small opportunity to shine a light on the human rights abuses taking place in West Papua came when a UN human rights panel issued a statement condemning racism and police violence in the region, resulting in a rare apology from the Indonesian police for one incident in particular.

There is also hope in the expression by the Indonesian foreign ministry that it will allow the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to visit West Papua. However, civil society are skeptical that the UN visit, if it takes place, will result in concrete changes.

“It is not new,” says Harsono, referring to previous invites that were not followed up with visas or details. “I won’t believe it until I meet them in Jayapura, until I see them in Papua.”

Meanwhile the election campaign is gathering steam, with the Nduga incident becoming a campaign issue, spurring increased nationalist sentiment against West Papuans. Unfortunately, there may be little that either Jokowi or his opponent – former military general Prabowo Subianto, who has a checkered record due to his involvement in East Timor – can do to change the plight of Papua.

“Whoever the president is, he will be in a difficult position since all political forces in Indonesia, whether the nationalist, the military or Islamic groups, seem to be reluctant to address the human rights issue,” says Ruhyanto. “It remains a marginal topic that only concerns a handful of activists and academics.” (*)

Nithin Coca is a freelance journalist who focuses on social and economic issues in developing countries, and has specific expertise in south-east Asia.