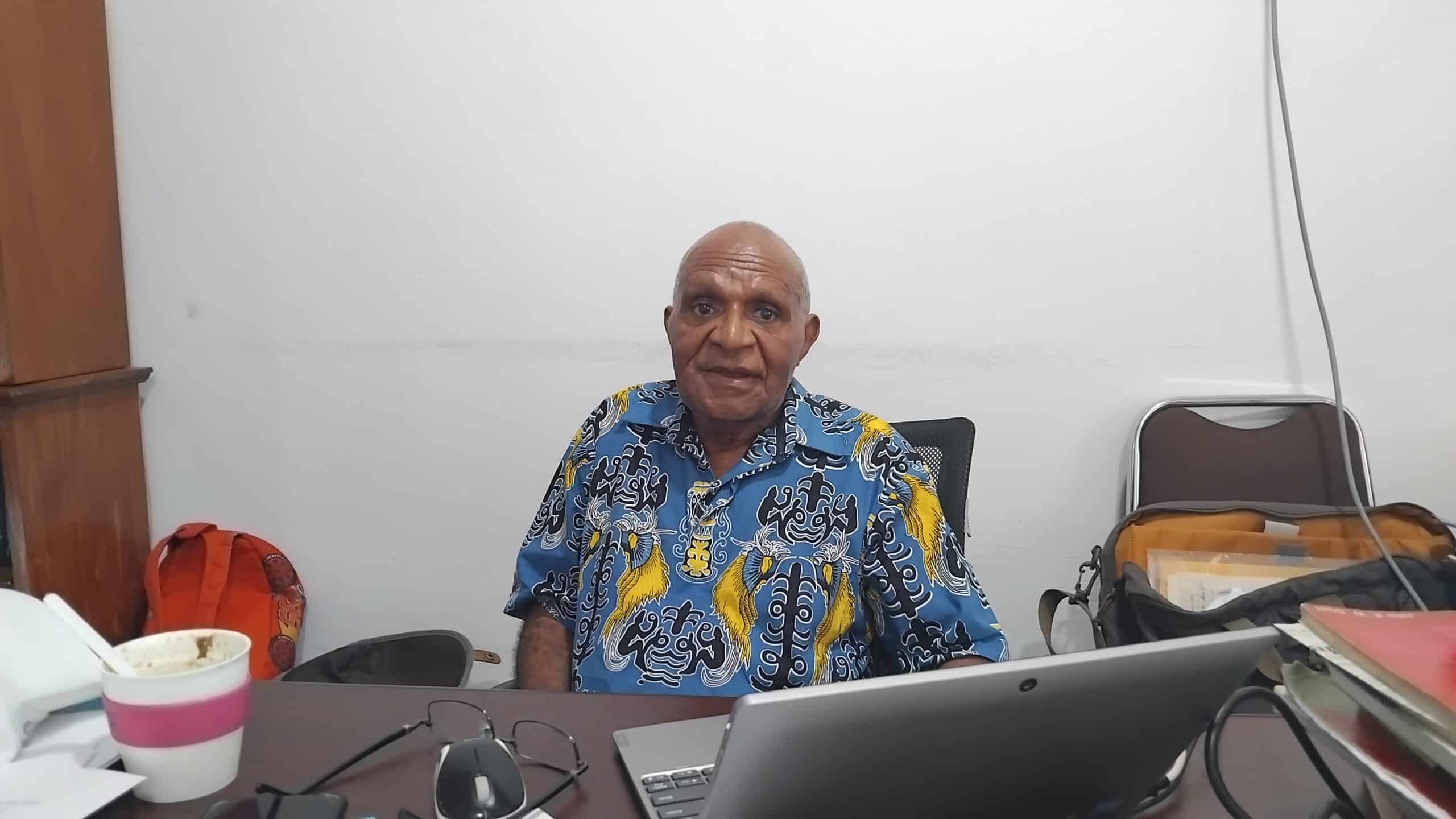

By Dan McGarry

LAST month, New Zealand-based analyst Jose Sousa-Santos commented on Twitter that “Indonesia’s attempt at buying support from the Pacific region seems to have little to no impact on Melanesia’s stance on [West] Papua.”

That’s one of those pesky observations that’s neither entirely right nor entirely wrong. The truth is: Indonesia is winning almost every battle… and still losing the fight.

Conventional wisdom used to be that Indonesia had built an impregnable firewall against Melanesian action in support of West Papuan independence.

Its commercial and strategic relationship with Papua New Guinea is such that PNG’s foreign affairs establishment will frankly admit that their support for Indonesia’s territorial claims is axiomatic. Call it realpolitik or call it timidity, but they feel that the West Papuan independence doesn’t even bear contemplating.

Widespread grassroots support and its popularity among progressive up-and-comers such as Gary Juffa don’t seem to matter. As long as Jakarta holds the key to economic and military tranquillity, Port Moresby’s elites are content to toe the Indonesian line.

The situation in Suva is similar. FijiFirst is naturally inclined is toward a more authoritarian approach to governance. And it seems that the military’s dominance of Fiji’s political landscape dovetails nicely with Indonesia’s power dynamic.

Many argue that Fiji’s relationship is largely mercenary. It wouldn’t flourish, they say, if the path to entente weren’t strewn with cash and development assistance. That’s probably true, but we can’t ignore the sincere cordiality between Fiji’s leadership and their Indonesian counterparts.

Same seeds

The same seeds have been planted in Port Vila, but they haven’t take root.

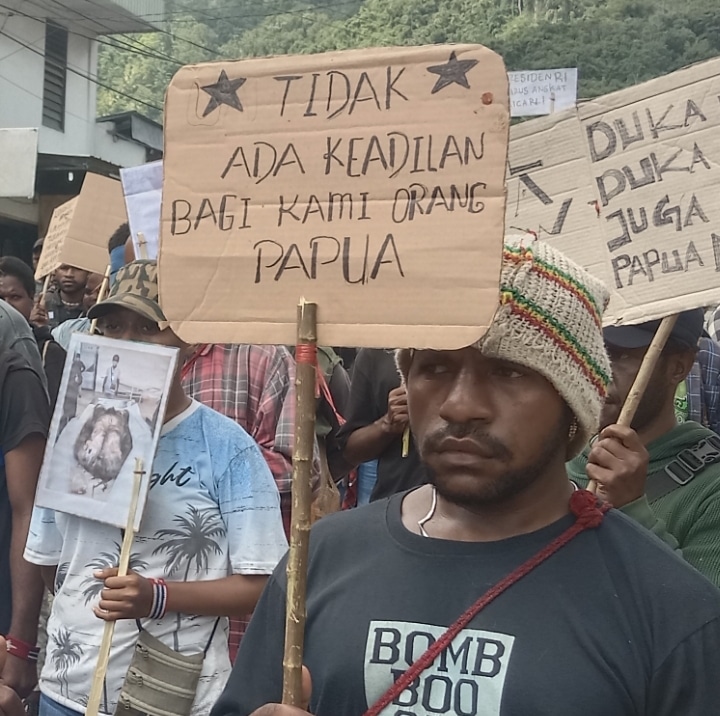

Until recently, Indonesia’s ability to derail consensus in the Melanesian Spearhead Group has ensured that West Papuan independence leaders lacked even a toehold on the international stage. In the absence of international recognition and legitimacy, the Indonesian government was able to impose draconian restrictions on activists both domestically and internationally.

Perhaps the most notorious example was their alleged campaign to silence independence leader Benny Wenda, who fled Indonesia after facing what he claims were politically motivated charges designed to silence him. He was granted political asylum in the United Kingdom, but a subsequent red notice—usually reserved for terrorists and international criminals—made travel impossible.

In mid-2012, following an appeal by human rights organisation Fair Trials, Interpol admitted that Indonesia’s red notice against Wenda was “predominantly political in nature”, and removed it.

Since then, however, activists have accused Indonesia of abusing anti-terrorism mechanisms to curtail Wenda’s travels. A trip to the United States was cancelled at the last moment because American authorities refused to let him board his flight. It was alleged that an Indonesian complaint was the source of this refusal.

Independence supporters claim that Indonesian truculence has also led to Mr Wenda being barred from addressing the New Zealand parliament. His appearance at the Sydney opera house with human rights lawyer Jennifer Robinson received a standing ovation from the 2500 audience members… and an irate protest from Indonesian officials.

Not all of Indonesia’s efforts are overt. Numerous commentators made note of the fact that Vanuatu’s then-foreign minister Sato Kilman visited Jakarta immediately before his 2015 ouster of Prime Minister Joe Natuman.

Lifelong supporter

Natuman, a lifelong supporter of West Papuan independence, was a stalwart backer of membership in the MSG for the United Liberation Movement for West Papua, or ULMWP. He was unseated barely weeks before the Honiara meeting that was to consider the question.

Kilman, along with Indonesian officials, vehemently deny any behind-the-scenes collusion on West Papua.

But even with Vanuatu wavering, something happened at the June 2015 Honiara meeting that surprised everyone. Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare stage-managed a diplomatic coup, a master class in Melanesian mediation.

In June 2015, I wrote that the “Solomonic decision by the Melanesian Spearhead Group to cut the baby in half and boost the membership status of both the ULMWP and Indonesia is an example of the Melanesian political mind at work. Valuing collective peace over individual justice, group prosperity over individual advancement, and allowing unabashed self-interest to leaven the sincerity of the entire process, our leaders have placed their stamp on what just might be an indelible historical moment.”

Since then, the sub-regional dynamic has undergone a transformation. Kilman’s administration suffered a collapse of unprecedented proportions following corruption charges against more than half of his government.

The resulting public furore seems—for the moment at least— to have catalysed a backlash against venality and personal interest.

If the rumours are true, and Indonesia did have a hand in Kilman’s palace coup, the tactic hasn’t worked since. A pair of no confidence motions—not very coincidentally on the eve of yet another MSG leaders’ summit—failed even to reach the debate stage.

Kanaky support never wavered

Kanaky’s support for West Papuan independence has never wavered, but given their semi-governmental status, and their staunch socialist platform, Jakarta would be hard pressed to find a lever it could usefully pull.

For his part, Sogavare has survived more than one attempt to topple him. His own party leaders explicitly referenced his leadership on the West Papuan question when they tried to oust him by withdrawing their support.

In a masterful—and probably unlawful—manoeuvre, Sogavare retained his hold on power by getting the other coalition members to endorse him as their leader. His deft handling of the onslaught has raised him in the estimation of many observers of Melanesian politics.

Some claim that his dodging and weaving has placed him in the first rank of Melanesia’s political pantheon.

In Vanuatu as well, once bitten is twice shy. Prime Minister Charlot Salwai raised eyebrows when he not only met with the ULMWP leadership, but accepted the salute of a contingent of freedom fighters in full military regalia.

The meeting took place at the same moment as MSG foreign ministers met to consider rule changes that, if enacted, will almost inevitably result in full membership for the ULMWP.

The MSG has traditionally operated on consensus. If these rule changes pass muster, this will no longer be the case. It is a near certainty that Indonesia will do its utmost to avert this.

Sogavare’s inspired approach

Sogavare has demonstrated an inspired approach to the situation: If the MSG won’t stand for decolonisation in the Pacific, he asks, what is it good for? This rhetoric has become a chorus, with senior politicians in Vanuatu and Kanaky joining in.

Sogavare is, in short, embarked on his own march to Selma. And he is willing to allow the MSG to suffer the slings and arrows of Indonesian opprobrium. He is, in short, willing to allow the MSG to die for their sins.

Whether we agree or not with the independence campaign, there is no denying the genius of Sogavare’s ploy. His willingness to sacrifice the MSG for the cause takes away the one lever that Indonesia had in Melanesia.

His key role in orchestrating an end run around the Pacific Islands Forum’s wilful silence is another trademark move. When human rights concerns were simply glossed over in the communiqué, he and others orchestrated a chorus of calls for attention to the issue in the UN General Assembly.

Manasseh Sogavare and his Pacific allies have found a strategy that is making the advancement of the West Papuan independence movement inexorable. As Ghandi demonstrated in India, as with Dr King’s campaign for civil rights showed again and again, anything less than defeat is a victory.

Without losing a single major battle, Indonesia is—slowly, so slowly—being forced from the board. (*)

The author is media director of the Vanuatu Daily Post.