Jayapura, Jubi/Quartz -Think of New Guinea and images of hilly jungles, winding rivers, and isolated tribal cultures might come to mind. What probably doesn’t: palm oil plantations. But maybe it’s time that they should.

Indonesia is already the world’s leading producer of palm oil, primarily from operations on Sumatra and Borneo. A key driver of economic growth, those operations have come into focus recently because of the fires—many set to cheaply clear land for palm oil and pulp-and-paper plantations—that have cast a persistent toxic haze over a large part of Southeast Asia, including Singapore, Malaysia, and southern Thailand. The pollution has led to respiratory problems, closed schools, and cancelled flights and events across the region.

Indonesia itself has the worst-hit areas. Its disaster management agency recently reported that the haze has caused acute respiratory infections in more than half a million people, and killed 10. Earlier this month the health agency of Palembang, Sumatra’s second-largest city, reported 19 infants had received treatment for the same condition, with one passing away. The government has announced plans for evacuation by warship to less polluted areas, with rains not expected before the end of November, thanks to the El Niño weather phenomenon.

The fires are “the biggest environmental crime of the 21st century,” wrote Erik Meijaard, who coordinates the environmental research initiative Borneo Futures, in the Jakarta Globe. Yet, he noted, “the government still hasn’t recognized how serious the problem is.”

For the 11 million people living on New Guinea, what’s happening on Sumatra and Borneo might be a glimpse into their own future. Indonesia’s loosely regulated palm oil industry sees the island as the next frontier, and a key to reaching the goal of producing 40 million metric tons by 2020, up from a projected 31.5 this year.

Reaching that goal will require lots of suitable land—an additional 12 million hectares or so. New Guinea has an ideal climate and is the world’s largest island after Greenland (Australia is classified as a continent, not an island). Indonesia claims the western half, which is occupied by its provinces Papua and the smaller West Papua. The nation of Papua New Guinea has the island’s eastern side. Palm oil producers are expanding there too, but there has been greater pushback from activists.

Besides hundreds of different tribes, New Guinea is home to incredible natural beauty and biodiversity, including the planet’s tallest tropical trees, biggest butterflies, longest lizards, and smallest parrots. The world has six species of tree-climbing kangaroos, and they’re all endemic to New Guinea. Scientists often discover previously unknown species on the island, including among reptiles, mammals, and plants.

Some forest areas on the Indonesian side of the island are officially protected from development. But the government has arbitrarily “de-protected” such areas in the past, Greenpeace has noted, including through a mandate (pdf) a few years ago.

The growth of the palm oil industry on Indonesia’s side has been swift, and that growth looks set to accelerate. A decade ago five palm oil plantations operated in West Papua, and by the end of last year there were more than 20. By March another 20 concessions were at the advanced stages of the permit process, with many more at the early stages. If all were developed, these plantations would occupy more than 2.6 million hectares of land, most of which are now tropical forest. The larger Papua province—holding 5.7 million hectares of forest land deemed suitable for oil palm—is seen as even more central to meeting Indonesia’s production goals.

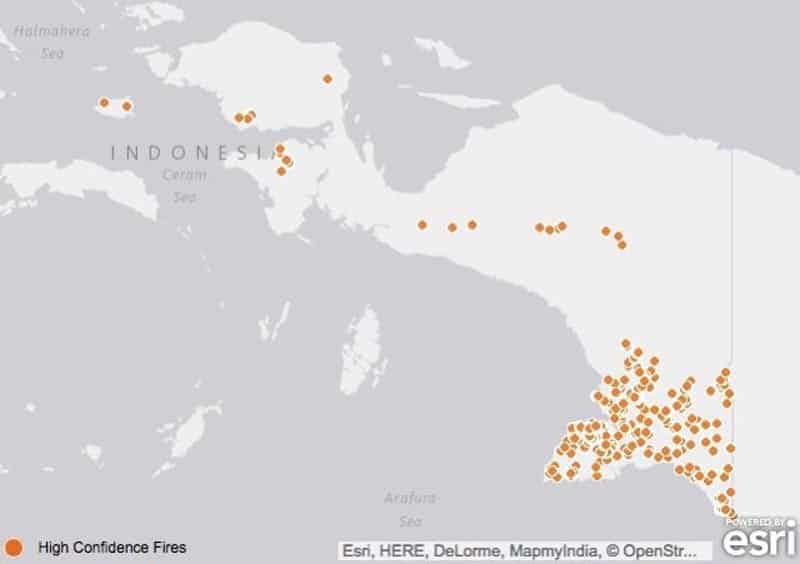

From Oct. 9 to Oct. 16, a particularly strong cluster of fires could be seen via satellite in the southeast corner of Papua province, according to Global Forest Watch. Most of those were in the Merauke regency, where the palm oil industry has a strong foothold.

To be sure, other commodities-based industries have also taken an environmental toll on New Guinea, including logging and mining, and often without sufficient benefit to local people (many of whom want independence from Indonesia, which they accuse of being exploitative). And other agricultural crops besides oil palms are being planted where forests used to be; indeed, the rate of Indonesia’s deforestation has surpassed Brazil’s.

But as on Sumatra and Borneo, with Indonesia’s palm oil industry comes increased deforestation and land-clearing fires producing huge amounts of smoke. Who sets the fires is usually a bit hazy, but typically more and more land is cleared and eventually taken over by neatly ordered rows of oil palms.

Far from seeing the destruction as a major concern, Indonesia’s government has defended deforestation on economic grounds, despite the activity making the archipelago nation—which has many low-lying areas, including much of the capital Jakarta—a major contributor to global warming and thus rising sea levels.

This month Indonesia announced its intention to form a palm oil cartel with Malaysia. The Council of Palm Oil Producer Countries would allow the two nations, which produce about 85% of the world’s production, to set their own environmental standards (or maintain the status quo), rather than being pressured into stricter “no deforestation” standards.

The smoke arising from Papua in the past few months has been noticeable enough from space to catch the attention of NASA, which captured the image atop with its Aqua satellite. The smoke over Papua and West Papua can’t yet compare to that seen on Borneo and Sumatra, where the palm oil industry has had longer to take hold, but it’s recently been strong enough to force flight cancellations and cast a haze in Sulawesi and as far away as Guam, a US territory more than 2,100 kilometers (1,300 miles) across the Pacific. (Steve Mollman)