By : Matthew Dornan

Jayapura, Jubi – In a post last September, we examined the first year of the Framework for Pacific Regionalism in the aftermath of the Port Moresby Pacific Island Forum leaders’ meeting. This year the action was in the Federated States of Micronesia, where for the first time, non-independent territories (New Caledonia and French Polynesia) were granted full Forum membership status.

Another first which went largely unnoticed was the inaugural standing meeting of the Forum Foreign Ministers in August (the meeting last year was a one-off affair; as of this year it becomes an annual occurrence). The foreign ministers’ meeting now serves as an additional filter on proposals submitted as part of the Framework for Pacific Regionalism. Whereas previously proposals were assessed by the Specialist Subcommittee on Regionalism (SSCR) tasked with reviewing regional public policy submissions and vetted by the Forum Officials Committee, they are now also considered (and vetted) by foreign ministers.

The prior meeting of foreign ministers appears to have influenced what was discussed (and not discussed) in the Forum leaders’ meeting. It may also have bolstered the influence of Australia and New Zealand given their foreign ministers’ interest in regional affairs.

Australia and New Zealand were vocal supporters of admitting New Caledonia and French Polynesia into the Forum, a move agreed by leaders despite the subject not having been raised through the SSCR process, opposition from pro-independence groups within those territories, and reports of unease among some Forum member states. Of course, the inclusion of the French territories also sits at odds with the original impetus for establishing the South Pacific Forum (as it was then known) in 1971. France at the time had prevented discussion of decolonisation and French nuclear testing in meetings of the South Pacific Commission. The Forum Communiqué announced this important development in one factual line — “Leaders accepted French Polynesia and New Caledonia as full Members of the Pacific Islands Forum” – in a possible indication of disagreement among some Forum members.

The decision to include the territories, although considered inevitable by some, in the immediate term looks a lot like a response to Bainimarama’s continued criticism of Australian and New Zealand membership of the Forum. The move provides an entry for another OECD country (beyond Australia and New Zealand) to influence Forum activities. It may not have been complete coincidence that events in Fiji overshadowed those of Forum over the weekend, with the removal of Fiji’s Foreign Minister from his position by Bainimarama mid-meeting (via email) followed by the concerning arrest of opposition and trade union leaders. Bainimarama will now take up the position of Foreign Minister himself.

Australian and New Zealand influence was also evident in other areas. The leaders’ communiqué’s positive spin on PACER Plus was especially striking. It made no reference to Vanuatu’s concerns about the agreement, nor to Fiji’s decision four days ago not to join the agreement (the communiqué did describe Fiji as having reservations regarding the text). However, it did confirm previous comments by PNG’s Minister for Trade that PNG would not sign up – a stance confirmed by O’Neill at the Forum.

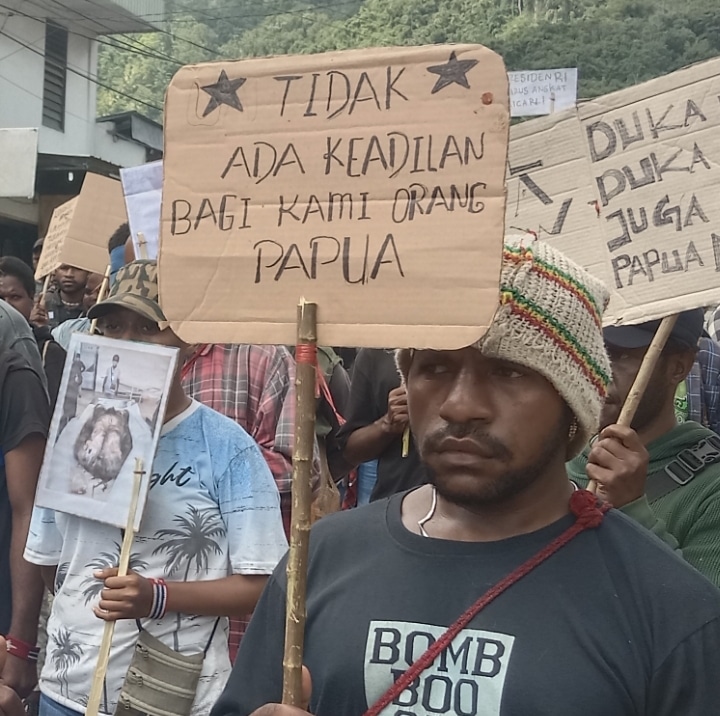

The relegation of West Papua as an issue was also notable. We might have expected to see West Papua given more prominence in the communiqué, given the fact that of the 48 regional policy public submissions that were received, 13 concerned West Papua. Instead, last year’s measured statement announcing the establishment of an independent fact-finding mission looks positively assertive when compared to this year’s communiqué, which simply states that leaders “recognised the political sensitivities of the issue of West Papua (Papua) and agreed the issue of alleged human rights violations in West Papua (Papua) should remain on their agenda” (while also agreeing “on the importance of an open and constructive dialogue with Indonesia”). The influence of the larger Forum members was likely at play here, including that of Australia, New Zealand, PNG and Fiji.

What of other issues discussed by leaders?

A positive development was the increased assertiveness of the Small Island States (SIS) group, which now also includes FSM. The leaders of the Small Island States (SIS) met earlier in the year in Palau and agreed upon a five-point Regional Strategy [pdf]– a significant component of which involves preparation of joint applications for funding from the Global Climate Fund (GCF). Not only will this be the first such joint application that the GCF will have received, but it has the potential to inform future activities by the Forum.

Fisheries management was again on the agenda, having been discussed at last year’s leaders’ meeting. Leaders endorsed the work of the Fisheries Taskforce in implementing the Fisheries Roadmap agreed in 2015. Importantly, leaders supported the view of the taskforce that there need be no change to the Vessel Day Scheme. This had previously been the source of some concern within the Parties to the Nauru Agreement Secretariat. The call by leaders for an expanded focus on coastal fisheries is a positive development.

As occurred last year, the communiqué discussed the importance of climate change for Forum island members. Although bold, there was not a great deal that was new here. An exception was leaders’ agreement on a Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific [pdf], which aims to integrate the region’s climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction frameworks into one. This followed bungled efforts last year to do the same, which saw leaders reject a draft given opposition by some member states to the detail of that text. The voluntary nature of the framework agreed this year was no doubt helpful in securing leaders’ agreement. The framework has nevertheless been criticised for not doing enough to integrate adaptation and disaster risk reduction.

Widely reported in Australia was the PM’s announcement of $80m over three years for disaster response, which adds to the $300m over 4 years already announced for climate adaptation in the region. Although that figure sounds impressive, $75m per year ($300m over 4 years) is below that provided in 2013, 2012 or 2011 (in that last year, Australia provided just under $170m). It does nevertheless mark an improvement on the dismal $40m provided in 2014 (as discussed previously on this blog).

The communiqué’s reference to cervical cancer and ICT – two initiatives canvassed by leaders last year as part of the SSCR process – is especially notable. We criticised the proposals at the time for being vague; it was unclear what their regional dimension was. Read between the lines of this year’s communiqué and it would appear that leaders agree – they pointed out that, “while important, these issues do not require their continued discussion to be progressed”.

How does the 2016 Forum leaders’ meeting measure up? There was less potential for controversy than in 2015, when tensions over climate change between Australia (in particular) and New Zealand and Forum island members were prominent. Fewer leaders attended this year’s meeting (five Forum island leaders instead sent delegates). Leaders did discuss issues of importance for the Pacific, but the outcomes of those discussion were limited, with much of the communiqué repeating previous statements (with some notable exceptions, including on fisheries management).

In many ways this year’s outcome reflects the Framework for Pacific Regionalism’s success in attracting high level political engagement. Having very clearly set a political agenda for last year’s leaders’ meeting, the interjection of the foreign ministers this year would appear to have had a diluting effect in some areas, with the influence of Julie Bishop and Murray McCully evident on issues such as West Papua. Australian and New Zealand influence appears to have driven other decisions as well, including the status of the French territories. Whether such political engagement has the unintended effect of undermining future engagement with civil society through the SSCR process remains to be seen.

Author is Deputy Director of the Development Policy Centre. Tess Newton Cain (@CainTess) is a Visiting Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.